.

If you have any comments, observations, or questions about what you read here, remember you can always Contact Me

All content included on this site such as text, graphics and images is protected by U.S and international copyright law.

The compilation of all content on this site is the exclusive property of the site copyright holder.

I have no count of how many times I would cross the George Washington Bridge, then drive north on the Henry Hudson Parkway, passing the exit for Ft. Tryon Park and The Cloisters. It must have added up to a significant number in the 17 or so years that we've lived in New Jersey. Yet it was only last month that I finally made a visit there. And as I wrote in that entry, " while I'm sorry I didn't do so before it's clear my next visit will not have so long a delay. " Here I am, just a month on, making a return visit. This time I even have two friends with me. They're both first-time visitors to The Cloisters. Ripples are spreading . . . .

What a difference a month makes at this time of year. Autumnal tints of orange, amber, gold, and russet color the trees on the Palisades across the river, and the stately oaks around the museum.

What better way to begin our visit, than to listen to Spem in alium numquam habui, a 16th century motet by Thomas Tallis. A cycle begins as we settle in the 12th century Fuentiduena Chapel. The Forty Part Motet is one of the reasons the three of us are here today. I want to listen again, Carol is a harpist, and Ann is especially fond of Baroque music. There's only one more month as the sound installation concludes on December 8th.

image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In the chapel I am again taken by the lion trampling on an evil dragon.

The three of us are agreed that the Unicorn Tapestries is next on our visit. Ann and I amuse ourselves identifying plants and flowers in the unicorn tapestries, also finding birds, a squirrel, dragonfly and butterflies. And as we exit, passing through the Nine Heroes Tapestries room what does Carol point out to us but King David and his harp. Of course. She's a harpist.

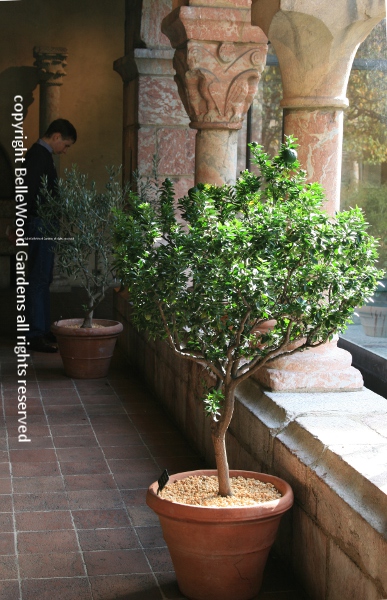

Our path takes us around the Cuxa Cloister. Last month it was open, and visitors could walk on the crossing paths among the flowers and peer into the central fountain. The fountain is now boxed in for winter, and the open cloisters on the garden's perimeter have also been closed off with transparent panes. The area is still flooded with light, and even more potted plants have been brought out for a sheltered, sunny, conservatory type display.

In addition to the rosemary plants I saw last month there are now an olive tree with dusty gray-green leaves, and several citrus trees, in fruit.

We continue around the cloister to reach the Langon Chapel and the stairs down to the lower level and the Bonnefont Cloister. This first takes us past the Pontaut Chapter House.

Built in the 12th century for monks of the Cistercian abbey at Pontaut, in Aquitaine, I love the geometry of this space. It needs no further embellishment to decorate it.

The Bonnefont Cloister remains open and accessible. The hops have been harvested, and the beds of of plants with culinary, medicinal, and craft uses are looking distinctly ready for their winter rest. Not shabby, mind you, for these gardens are very well tended.

Notice that the 75 year old espalliered pear tree, well sheltered as it is by the protective wall behind it, has now begun to turn from green. A leaf here, a leaf there - winter is coming.

Christina Alphonso, administrator at The Cloisters, was gracious enough to answer a few questions that I had about the four quince trees. She wrote: "The Smyrna quince trees in Bonnefont were planted in the 1950s. We do not harvest the quince, but pick them up as the fruit falls from the trees. Our trees continue to bear a crop, but the fruit is thinned in the summer to reduce the stress on these venerable trees. Windfalls of the ripe fruit are available to the staff and volunteers, although few fruits ripen soundly enough for use. Many of us simply enjoy the fragrance of the ripe fruit, which we leave on our desks."

Here's some background of the culinary history of the quince from my book, Preserving Memories: Marmalade, it is frequently said, is where preserving began. In ancient Greece, in the 1st century A.D., Dioscorides described how to tightly stuff melomeli, quince, into a container of honey and let them sit for a year after which they would soften. The "recipe" is in his De Materia Medica because sweetened quince paste was used as a digestive aid. Three centuries later, in Opus Agriculturae, Palladius suggested cooking peeled, cored, shredded quince in honey, sprinkling it with black pepper. Fast forward to another recipe, this time from late 14th century France (Le Menagier de Paris) which continues to combine quinces, honey, and spices. Marmelada was exported to England towards the end of the 15th century, and recipes for making it at home soon followed. It is in England (A Leechbook) that a written recipe first mentions sugar. The first of three recipes for chardequynce (good for the stomach, the author says) is a concoction of quinces and pears boiled in ale, mashed in a mortar, then sieved, mixed with honey flavored with black pepper, boiled again and stirred vigorously while it cooks. When stiff it is flavored with cinnamon and ginger, allowed to cool, and then sliced. This would be more along the lines of fruit leather, but more heavily seasoned than contemporary tastes prefer. It would have been served as an after-dinner digestif and sweetmeat. The next recipe uses 2 parts honey and 3 parts sugar, "and shall this be better than the other . . ." The third recipe "is the best of all" and uses equal parts by weight of sugar and quinces. . . . . it is from the Portuguese language, where melomeli became marmelo, that marmalade got its name.

Though even less well known than the quince, I hopefully asked if there are any medlar trees at The Cloisters. One spring I had seen a medlar tree in bloom in a Garden Conservancy Open Days garden in New Jersey. And a friend, also in New Jersey, has a tree. He once sent me a few fruits. It seems like an especially suitable tree for The Cloisters. And indeed, it is. Again, Christina had the answers: "We have three medlar trees planted below the east wall of the Bonnefont Cloister, which we intend to move to our Orchard later this fall; the cultivar is "Nottingham". The fruit is harvested only after the leaves fall, and must then be bletted (stored for several weeks in a cool, dark spot until they become rotten-ripe). Once the pulp is soft, it can be eaten out of hand. We'll blet our small crop and offer it to staff for tasting as we have in the past."

Leaning far over the perimeter wall of the cloister I did indeed see the medlar trees and their fruit. And when we left I looked for a path which led to the trees in their inconspicuous location. From there I was able to get a better image of the strange little fruit.

.

I find The Cloisters a wonderful place with something for many interests. The architecture creates a spirit of place that transcends the word "museum." There's the sense of history, of course, and religion imbues the collections. Magnificent art in any media you can think of. Carvings, statuary in stone and wood. Tapestries. Paintings. Ceramics. Stained glass. Illuminated manuscripts.

And for the gardener, beyond the living collections in the cloister gardens, to trees and flowers in the tapestries, even columns with their acanthus leaf capitols - art and nature joined.

Back to Top

Back to November 2013